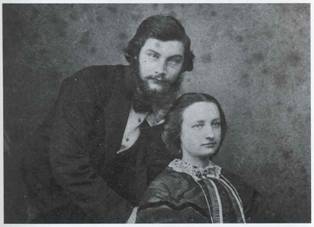

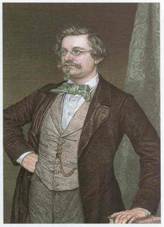

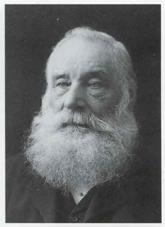

William Perkin in black-and-white: a self-portrait at 14. Perkin the inventor with his second wife Alexandrine in 1870. Dr August Hofmann, who

thought his protégé was wasting

his time.

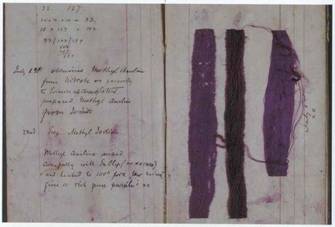

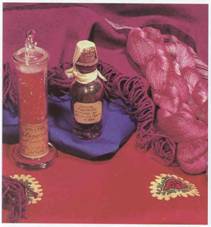

‘The torch which enlightens the path of the

explorer in dark regions of the interior of the molecule’ but to the dyer all that

mattered was brilliance: a recipe book from 1868.

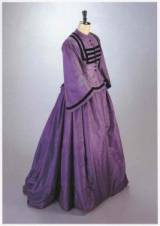

The mauve, alizarin,

crystals and cloth that changed the colour of our streets. The Perkin Medal has since

been won for innovations in nylon, vitamins and medicines. The sketches show the

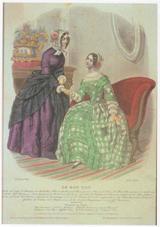

expansion from 1858 to 1873. ‘Luring on

foolish bachelors to sudden proposals’: a silk dress dyed with original mauve in 1862. ‘A miracle that

Perkin did not blow himself and Greenford Green

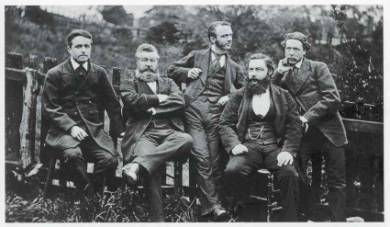

to pieces’: Perkin (second from right), his brother Thomas (second from left) and fellow dyemakers delight in their continued good health in the field outside their dye works. The house that mauve built. Fame at last: at the

British Association meeting in 1906, Perkin’s

illustrious colleaques paid tribute to

a pioneer, but his name would soon be

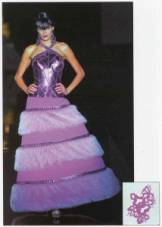

forgotten. What dyes did next: a catwalk model in Paco Rabanne, and a stained micrograph of the serpentine cords of tuberculosis bacteria. The grand old master at

68. An object of ridicule, an object of pride: gaudy, fugitive and poisonous, but the new colours proved irresistible to fashionable

Source: Garfield, Simon: Mauve – How One Man

Invented a Color that Changed the World, New York, London: W.W.

Norton & Company.